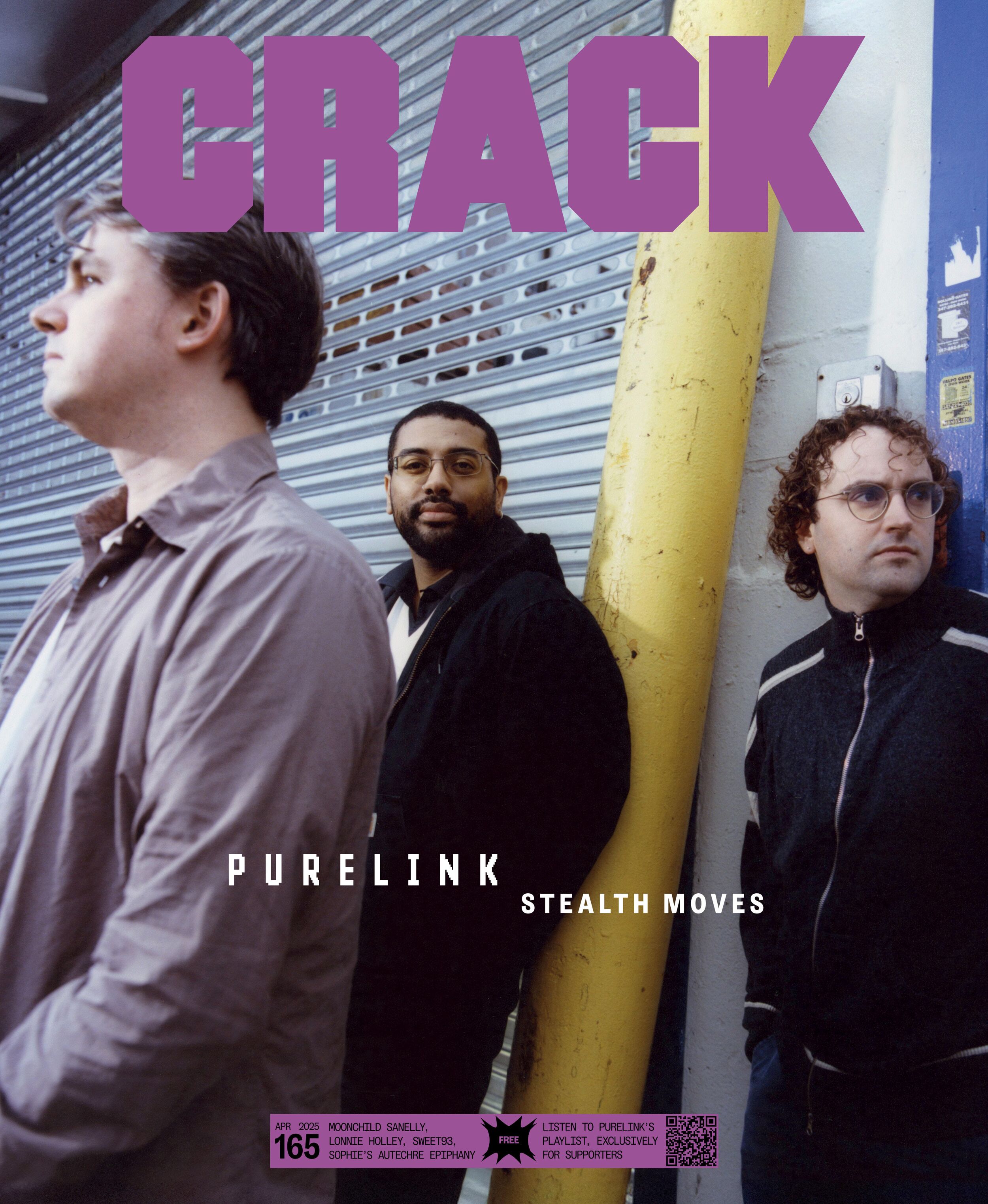

Tygapaw: Burning bright

“Maybe I’m a singer-songwriter trapped in a rave kid,” Dion McKenzie, better known as Tygapaw, remarks during our conversation. Although they’re joking, their observation is spot on. “It’s just the tools that are different. I’m a singer-songwriter, but I want to use a synth and a drum machine and make pulsing, hard, driving music.”

Tygapaw’s pairing of diary-like and socio-politically informed ruminations with rattling electronic soundscapes has built them a dedicated following. With each release, they dig deeper inwards, their productions getting sharper and their concepts more raw. On their first two EPs, 2017’s Love Thyself and 2019’s Handle With Care, Tygapaw explores their queer identity, domestic violence and colonialism from their Jamaican upbringing, and self-preservation through a sound palette that glides confidently through techno and Baltimore club to baile funk and experimental electronica. Their last EP, Ode to Black Trans Lives, was released during the height of Black Lives Matter protests as “a sonic reminder that Black Trans Lives Matter”. A collaboration with scholar D-L Stewart, it further demonstrates their propensity to use music as a tool to connect, process and document – all through their rave kid lens.

Despite slow recognition from music media outlets, Tygapaw has persistently spent the past eight years dedicated to their craft, employing an independent DIY approach. Their music has taken them on tour across several countries, one of them being Australia where I saw them last January shortly before the Covid-19 lockdown. Before we spoke, I scrolled through my phone’s camera roll to a typical shaky club video showing Tygapaw playing at Radar in Melbourne, their outline blurred by a combination of twitchy lighting and the bobbing heads of excitable dancers moving in tandem. It was an intimate show of people who were seemingly mostly fans rather than casual party-goers, Tygapaw’s infectious energy drawing them up close to them.

© Avion Pearce

Not long after that show, they returned to the US and their bustling calendar was reconfigured. They swapped planes and trains for the solitary confines of their bedroom-turned-music studio in Brooklyn; where they are when we speak over Zoom. Rosy pink walls line the room and stand in stark contrast against their lime green hair. They sit beside a beige electric guitar and a recently purchased Studiologic Sledge 2.0 synthesiser. Primarily considering themselves a producer and musician, Tygapaw feels most at home in their studio.

Growing up in Mandeville, a small town in west-central Jamaica, Tygapaw was constantly drawing. They eventually moved to New York in 2002 to study at Parsons School of Design. Despite their inclination towards visual art, music was always their foremost passion and as soon as they graduated, it shifted to their main focus. Before becoming ‘Tygapaw’, they had earlier stints in a band called M.O. and in a rap duo called Kowabunga Tyga, where they taught themselves how to play instruments and develop a stage presence that masked their introverted persona. “The first photos of me holding a guitar on stage I was just looking down, I was petrified,” they reminisce. But their youthful shyness was overshadowed by their seasoned determination. “You have to just jump in, because if you want to do it, you have to overcome a lot of those fears and phobias.”

Their beginnings as a musician coincided with major life shifts, primarily learning how to adjust to the systemic racism woven so tightly into the fabric of North America. “I didn’t quite understand the severity of racism here, and those aspects of learning and experiencing another level of trauma added onto trauma already experienced from me coming from a colonised island,” Tygapaw explains. They describe how they felt as if they were on a hamster wheel, constantly exerting themselves to no avail. “You’re in motion, you’re exhausted and the weariness is just a lot – that wears you down.”

© Avion Pearce

For Black and POC artists, working through racial trauma and interrogating the systemic forces in the music industry that work against them is an additional barrier to entry they face over their white counterparts. “It takes so much strength and courage to just be fiercely independent and know who the fuck you are and forge forward with that attitude,” Tygapaw says resolutely. “There are constant obstacles that are there to do nothing but stop you in your tracks. Nothing else but to destabilise you and reduce you down to nothing. There are plenty of those kinds of tactics.”

“It takes so much strength and courage to just be fiercely independent and know who the fuck you are”

For Tygapaw, the path has been rocky and long. Learning how to dig themselves “out of a hole that the system wants to put you in” and understand their surroundings and what it means to survive – and thrive – in North America as a Black queer person, has taken time. But they refuse to let it define their story, fixating instead on liberation. “That’s why I go beyond hard,” they assert with a smile. “I go beyond the threshold because I’m not going to be a statistic. I’m not going to let whatever projected circumstances ultimately be the conclusion of my life. I’m going to take charge of it.”

Tygapaw’s earlier music career was also shaped by them finding their “queer footing”. In search of community, they began running their own queer club nights in Brooklyn, Fake Accent and later the more Caribbean-music focused Shottas and No Badmind, with the intention of creating a nurturing environment free of intimidation. They began learning about the queer and Black origins of club culture and became enamoured. “I lost my mind, like this is incredible,” they recall and laugh. “I’m never, ever going to perform femininity again. I’m never going to act like a straight person, I’m not – I’m gay! Like fuck that shit – these are my people.”

© Avion Pearce

“I’m never going to act like a straight person, I’m not – I’m gay! Like fuck that shit, these are my people”

Today, Tygapaw is feeling much more at peace with who they are. “I feel free,” they coolly reflect. “And that’s that absolute feeling of liberation and how queerness is such a freedom. It’s such a warm feeling, discovering that there’s a space that exists, that you can feel connected to, you can feel safe within, you can feel community. And that was my introduction into starting the process of finding my way to techno honestly.”

These discoveries define their latest album, the aptly titled Get Free, released through forward-thinking Mexican label NAAFI. Created within two months over the turbulent US Summer, the LP is an expression of Black liberation, created to uplift listeners. “It’s about denouncing ideas of self-sabotage. Denouncing doubt, removing that from one’s psyche and challenging aspects and parts of me that have been conditioned to always second guess myself, and really stepping deeper into my research and discovery into the world of techno because it’s vast,” Tygapaw excitedly explains.

The album celebrates the classic Detroit techno sound, but it also draws inspiration from Black music television, through the influential Detroit television show The New Dance Show and from music videos by the likes of Rufus and Chaka Khan. Musically, Tygapaw’s research into techno’s pioneers is evident, putting a contemporary twist on time-honoured 4/4 beats and thunderous synth stab motifs from artists like Underground Resistance and Jeff Mills. In contrast, on their collaborations with artist and writer Mandy Harris Williams, Tygapaw departs the dancefloor and looks skywards. Cloudy, amorphous synth pads act as a pillow for Williams’ poetic musings around the theme of freedom.

Get Free is Tygapaw at their most confident, the culmination of years of self-discovery and self-education. I ask them where their fearlessness to thrust themselves into unknown territories and be their own guide comes from. “I feel like I attribute that to me being Jamaican. We’re a bit bold, you know?” they laugh.

But they also have a “Fuck it, Imma try it” attitude. “If you can’t find something, you make it. I mean honestly, that’s my ancestors. That’s my shit. If we can’t have access to it, we make the thing, we create it.” Tygapaw credits this mentality to the success of Fake Accent, which after five years of being a home for like-minded queer POC, will be expanding into a record label. With labels often structured in a way that exploits artists, Tygapaw is still in the learning phase, researching how to run Fake Accent ethically and independently. Despite the trepidation of entering unknown territory again, they’re driven by their observation of the lack of Black-owned electronic labels, and is eager to occupy that space.

“Getting outside of my comfort zone and being uncomfortable is a part of growth, and I’m very much a person that’s comfortable with that idea, so I’ll always put myself in that position. Like, ‘OK great, this is going to be uncomfortable but it’s a learning process’ and then I will surely learn a lot, and be able to take from it and build.”

Outside of developing Fake Accent into a label, Tygapaw is focused on staying inside their rosy-pink bedroom studio, continuing to produce music and build a live set in preparation for the eventual return of nightlife. They’re also in the mindset of manifesting, setting their intentions towards film scoring, more studio projects and more tours. I express how we’re going to see ‘Tygapaw 2.0’ emerge once nightlife reopens.

“I like that,” they laugh. “Hell yeah, I agree. If anything, I just feel like I know I want to leave an archive of music that’s reflective of the time that I spent on this earth and what we’ve all been exposed to. Leave it as an artifact for the children so they can hear what the fuck is up, so they know what they need to do to start the revolution. If they don’t start the revolution now, we gotta leave them clues to sort that out, and be like keep on it, be diligent you know?”

Photography: Avion Pearce

Get Free is out now on NAAFI

ADVERTISEMENTS